The story begins in 1999 with a mango tree in Hinche, Haiti.

Saint Fleur Junior Charles, or simply Junior as most people

call him, was 16 years old when he jumped into a tree, fell

and broke his spinal cord. Nine friends carried him

unconscious to the nearest hospital. When Junior woke up, he

had no recollection of his fateful fall. His mother, Anne

Marie Charles, a housemaid in Port-Au-Prince, 100 miles away,

arrived later that evening and sat by her son’s side.

According to Junior, now 32, she remained there for the next

two years.

Paralyzed from the waist down, Junior spent the next two

years in bed, sometimes his own, sometimes in a hospital. He

said every doctor he and his mother met agreed that Junior

would spend the rest of his life bedridden. He withdrew from

school, and Anne Marie, a single mother, left her job to care

for him. Junior said that during this period, he woke up

every morning hoping he would die.

Meanwhile, Anne Marie, now 69, whom her son describes as a

faith-filled woman, prayed for an answer. Then one day,

Junior said, it came.

Frustrated with local doctors, his mother decided they would

leave Haiti for the island’s more prosperous neighboring

country, the Dominican Republic. Anne Marie reasoned that the

doctors there were better trained and equipped with more

resources at bigger, cleaner hospitals.

Peter Dirr, a board member for Medical Missionaries, a global

health organization based in Manassas that runs St. Joseph’s

Clinic in Thomassique, Haiti, confirmed that Anne Marie’s

instincts were good.

“The people living in the central plateau off Haiti are some

of the poorest people in the Western Hemisphere,” he said.

“In the Dominican Republic, people are poor but many times

better off.”

Junior trusted his mother, but was worried that they lacked

passports and visas.

“How were we going to go to another country?” he asked.

Anne Marie insisted they would find a solution. A week later,

a woman Junior had never met came to the hospital and handed

him an envelope containing $500, a small fortune in Haiti.

Lourde, as he learned she was named, only said that she knew

he needed it.

Anne Marie used the money to hire a truck and driver to take

them across the border. Yet before Junior and his mother

could leave for the Dominican Republic, they had to go

shopping. Anne Marie had no shoes, and Junior had nothing but

bathing trunks.

When the truck Anne Marie hired arrived, she put a mattress

in the back for Junior since he could not sit up or join his

mother in the cabin of the pickup. Then they were off.

“We had no idea where we were going,” Junior said.

The driver pushed through until the truck could go no

farther. Because it was the middle of the rainy season, the

rivers had flooded and turned the dirt roads into thick mud

that the truck could not pass through. Anne Marie went

searching for someone to help carry Junior to shelter. She

found four strangers willing to carry him over two rivers to

the nearest clinic.

Three or four hours later, they met one of the people Junior

credits for changing his life: Father Jack O’Hara, now

parochial vicar at Holy Family Church in Dale City.

“Father Jack really adopted Junior as his godchild,” said

Dirr.

Father O’Hara was serving at the Arlington Diocese’s mission

in the city of Bánica (where Father Keith O’Hare and

Father Jason Weber now serve) when he recognized Junior’s

need for help. He facilitated the medical attention Anne

Marie desperately wanted for her son. But just as in Haiti,

doctors in the Dominican Republic said he would remain

bedridden. Father O’Hara and Anne Marie were not ready to

give up, though Junior said he was convinced he would be

confined to a bed for the rest of his life.

“I didn’t cry because my mother was sadder than I was,” said

Junior. “I had to have courage.”

Then came the fall of 2001 when an American doctor in Santo

Domingo suggested amputating one of Junior’s legs and

operating on the opposite hip to make it possible for him to

use a wheelchair.

The plan worked.

By winter, after Junior had become comfortable in his

wheelchair, Father O’Hara began asking him what he wanted to

do. He said he wanted to finish high school.

Junior went back to high school and graduated in 2006. With

Father O’Hara’s assistance, he went to college, studied

Spanish and English at night and graduated first in his class

with a degree in public administration in 2010.

But even after the operation, his medical woes were not over.

One day in 2008, Father O’Hara noticed that Junior’s eyes

looked strange. He had a fever and tightness in his chest.

Junior had a bone infection that led to sepsis. Father O’Hara

arranged for Junior to go to St. Joseph’s Clinic, where

American doctors from Medical Missionaries were visiting.

After what Dirr described as a “serious surgery,” Junior

rested in the hospital for a week and then at home for

another two.

Three and a half years later, after Junior graduated from

college and could not find a job, he began volunteering at

St. Joseph’s Clinic as an assistant administrator. By July

2012, he was hired full-time while he studied at night to

pursue his law degree.

Father O’Hara said Junior’s outstanding efforts and his

willingness to learn eventually led to his promotion as

hospital administrator. Junior took the initiative to

organize the hospital’s medicine and supplies, which had

previously been kept unalphabetized on the floor, and to

digitize thousands of patient records. He also started a

garden, allowing patients to get staples like beans and

plantains after a visit to the doctor.

Through partnerships with the University of Notre Dame and

Washington University-St. Louis, the hospital now has

programs that provide the community with fortified salt,

clean water and high-protein food supplements for

malnourished children, among other services. Under his

administration, Junior said the hospital sees about 50

patients a day, or 25,000 patients every year. Annually, an

average of 500 babies are born at St. Joseph’s Clinic.

Impressed by his success, Medical Missionaries has brought

Junior to Manassas two summers in a row. Last year, he came

for the organization’s annual fundraising gala. This July,

Dr. Gary and Sharon DeRosa, who are parishioners at All

Saints Church in Manassas, hosted Junior at their home for a

week. During his trip to Virginia, he met with Medical

Missionaries staff, went to doctor and dentist appointments

and spent time with Father O’Hara, who continues to mentor

him.

“In Hinche, I had no spiritual experience. It was my mother

who had a lot of faith,” Junior said. “I remember going to

get my MRI and Father Jack telling me, ‘You need to have

faith.’ Now faith guides me every day. I have no fear. I used

to go to bed without saying my prayers. Now I wake up to pray

daily. I thank God. I thank my mother. I thank Father Jack

because I’m alive. I went through some really terrible times,

but I like my life now.”

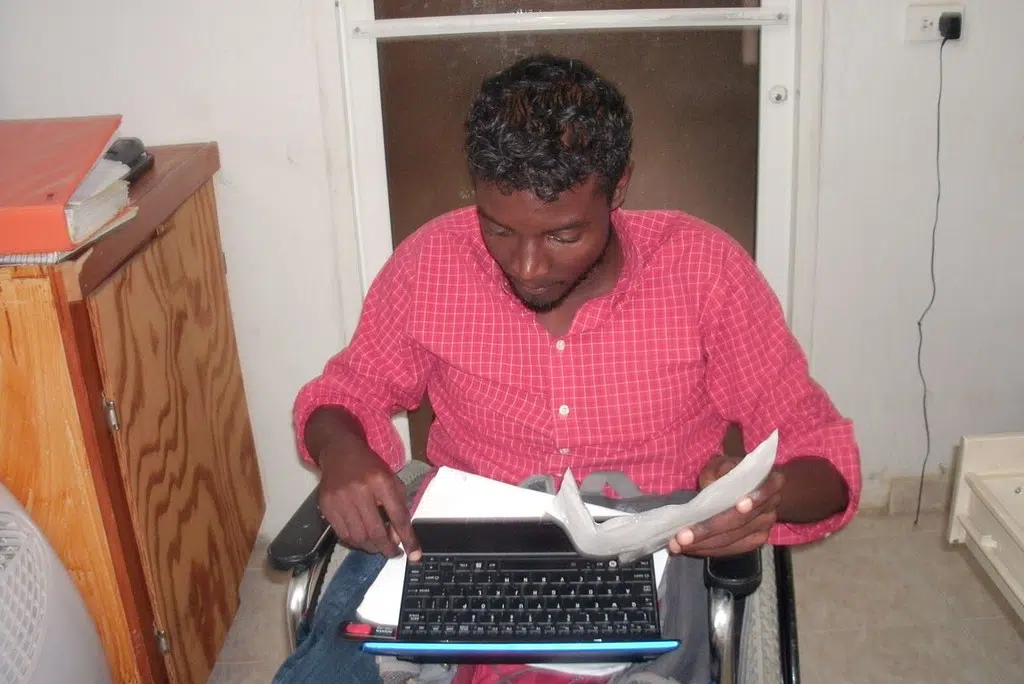

Today, Junior spends his days and nights working, praying,

taking care of his mother and writing a book on handicapped

law. He hopes to one day become a judge who rules on cases

related to rights for the handicapped.

“If you have faith, medicine works faster,” said Junior. “You

have hope. No stress.”

Find out more

To learn more about the Medical Missionaries of Manassas or

make a donation, go to medmissionaries.org. To donate to

Bánica Mission, go to banicamission.com/donate.

Stoddard can be reached at [email protected].