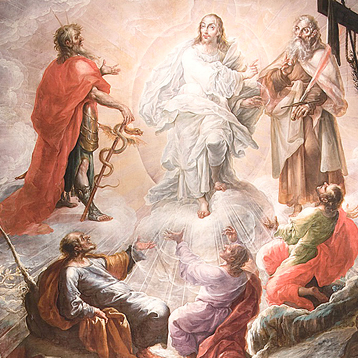

NEW YORK — A 28-foot-tall altarpiece, loaned for the first time ever from a Mexican cathedral, towers in the atrium of the Lehman Wing of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Visitors can savor the details of the dramatic story of Moses and Brazen Serpent on the lower story and then view the luminous Transfiguration in the upper.

The composition, signed and dated 1683, is not only grand, but unique. Cristobal de Villalpando signed himself as the “inventor” of the altarpiece, the only painting that juxtaposes those two subjects. Above, Christ in radiant white raiment appears to His three dazed apostles over Mt. Tabor, flanked by the Old Testament prophets Moses and Elijah as recounted in Matthew 17:2. Villalpando added two telling details to this oft-depicted miracle: on the right, a cross adorned with the instruments of Christ’s Passion, and on the left, the snake-encircled staff in Moses’ hand.

Below a sharp horizon, the Israelites, having rebelled against God, are dying from a plague of snakes in a rugged landscape of rocks and trees. Moses, following God’s instructions, erects a bronze image of a serpent in the wilderness to heal the snake-bitten multitude (Nm 21:8-9). Opposite Him a priest (Aaron? Eleazar?) gestures toward a penitent man kneeling and looking up to the effigy.

An angel in flight holds the text: “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert, so must the Son of man be lifted up:/That whosoever believeth in him may not perish, but have life everlasting.”

Encounter of two cultures

The home chapel of this altarpiece in Puebla Cathedral was the music chapel, where Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla, chapel master from 1629 to 1664, composed villancicos (Christmas carols) and sacred motets that infused Old World polyphony with the music of New Spain’s non-white populations, both African and Aztec.

Later, centered on a miraculous statue of “Christ at the Column,” the chapel became the site where the reforming bishop, Fernandez de Santa Cruz, heard Lenten confessions in the two weeks before Easter. Penitents would gather in the chapel next to the “Moses” picture of divine wrath and repentance. The brazen serpent story figured in Holy Week Mass readings then, as it often does today.

Villalpando departs from European tradition in depicting Moses. The patriarch wears a full suit of armor, conquistador-like, and points up toward the Brazen Serpent (i.e., the Cross) while looking over his shoulder at the stricken Israelites. This could be a reference to the bishop, who put on armor and prepared to march to the rescue of Veracruz when English pirates invaded it in 1682.

Part of American history

The Villalpando exhibit, which closes on the last day of National Hispanic Heritage Month, marks a welcome departure for the Metropolitan Museum. The Met has only had a Latin American art curator since Ronda Kasl was hired in 2014. Since then, Kasl said the museum has acquired eight paintings in this field. New discoveries proceed apace: an unknown major altarpiece by Villalpando recently came to light at Fordham University.

Villalpando, born in Mexico City around 1649, drew upon European traditions without ever leaving New Spain. Biographers deduce that his 10 closely spaced children left no time for a trip abroad. He mined the available trove of engravings after the compositions of Rubens, the defining painter of the Catholic Reform in Antwerp — then under Spanish rule — and the fluid brushwork and saturated color of the Seville School of painting, transforming these into a wholly original style.

Villalpando’s creative imagination and grasp of Old Testament-New Testament theological links also sparkle in the canvas of the “Holy Name of Mary” dated c. 1690-99. This subject relates to a feast of the church celebrated Sept. 12, long popular in Spain and its dominions.

The expectant Mary kneels below a haloed inscription of her name, surrounded by angels, some very corporeal, others fading into transparency. A unique feature is the Ark of the Covenant as a piece of Baroque gilded furniture on the left side. Just as the Angel told Mary the Holy Spirit would “overshadow” her, the same word “episkiasei” was used in the Greek Old Testament to describe how the glory of God overshadowed the tabernacle and temple where the ark was kept.

Kasl said that the painter intended for people to “hear” in the imagination the sweet sound of Mary’s name when looking at this painting. “Just my thought,” she added — but given the splendid musical heritage of New Spain, a tempting one.

Hamerman is a freelance writer from Reston.