The other week my wife and I went out on a date. After a hectic few weeks, our special time together had at last arrived.

All around us at the restaurant were other couples, out on dates. About halfway through the dinner, I began to notice something.

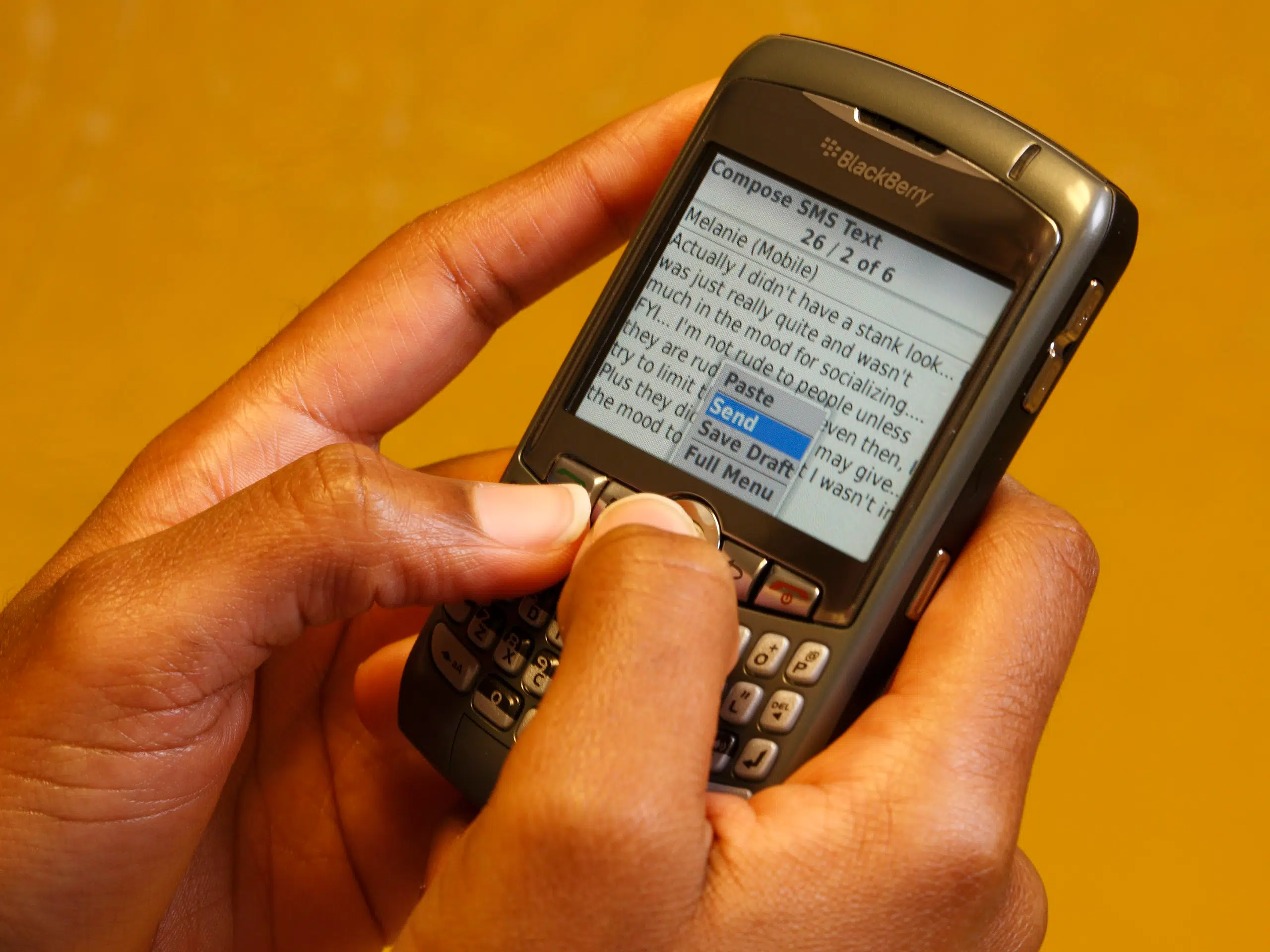

One of the spouses at a nearby table would stand up to use the restroom. Almost immediately, the other spouse would take out his or her phone, and then pocket it when the spouse returned, or leave it out on the table, or even continue staring at it. If it was the latter, the other spouse would take out his or her phone, in a kind of mutually assured destruction of the date.

How pathetic we all are, I thought to myself, alone at my table for a moment. We are not able to sit quietly in a restaurant — alone for one minute — without turning to our glowing rectangles. If this is how we act in public, God help us for what we’re all doing at home in front of our kids. And just as I had these profound insights, I wondered what the next morning’s weather was going to look like, and I pulled out my phone to check.

A few days later I was at Mass when, at the words of consecration, I saw a “first”: As the priest lifted the host above the altar, someone was texting. I see texting while driving all the time, but texting while kneeling was new.

Here we are: The choirs of angels are attending, and the miracle of transubstantiation is happening before our eyes. Here we are: The image of God is visible before me, in my beautiful spouse, as we enjoy time together. And yet again, we succumb to the desire to be in two places at once.

The protagonist of an Edward St. Aubyn novel might just speak for us all: “It’s the hardest addiction of all … Forget heroin. Just try giving up irony, that deep-down need to mean two things at once, to be in two places at once, not to be there for the catastrophe of a fixed meaning.” (St. Aubyn is a recovering heroin addict.)

Perhaps the deep-down fear of this catastrophe is what I glimpsed at that restaurant and at Mass. Perhaps we’re so used to being in two places at once that we can no longer bear the fixed meaning of a date, with our attention fixed only on our spouse, or Mass, with our focus only on Our Lord, or family dinner, fully present to our children.

This summer my family was blessed with the opportunity to see Pope Francis from a distance of about 10 feet, in St. Peter’s Square. Out came the phones. And right after the popemobile passed, we all looked down at our relationship inhibitors to post, tweet and text. After all, how could we submit to the fixed meaning of only being in one place, St. Peter’s Square — with our brothers and sisters gathered from the four corners of the earth — in the presence of the pope? We needed to run from that catastrophe.

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone,” wrote philosopher Blaise Pascal in his Pensées, more than 300 years ago. But today, anyone can sit quietly in a room alone, smartphone in hand, and if they choose, evade God and one’s own conscience in the process.

With St. Aubyn’s help, allow me to suggest a revised pensée that accounts for the addictive quality of our technology: All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone, content with the fixed meaning of being in only one place.

To be present — to God, our spouse, our children, or a friend — now seems to require that we first confess that we prefer being in two places at once; that we then beg for the grace to turn away from the heroin-like lure of our world’s escapes; that we embrace the poverty of being in only one place, and patiently receive the “fixed meaning” of the person — a resplendent image-bearer of the almighty God — before us.

The bill came. My wife and I thanked the waiter and got up to leave. My wife’s hand in mine, I glimpsed the truth — for a moment — with utter clarity: To be in one place is the most glorious thing.

Soren and his wife, Ever, are co-founders of TrinityHouseCommunity.org.