You might already know what icons look like – found in

churches and museums around the world, they are religious

images of Jesus, Mary or a saint painted on wooden panels,

usually featuring golden halos. They are beautiful, but have

you ever stopped to think how they were made?

Participants in a recent icon painting workshop at St.

Catherine of Sienna Church in Great Falls could tell you. For

the last three weekends, they spent almost 40 hours learning

about pigments, religious symbolism and eggs – yes, eggs.

Such is the life of an icon painter.

Thousands of years old, iconography is a labor-intensive art

form with specific steps, that have been perfected over the

years.

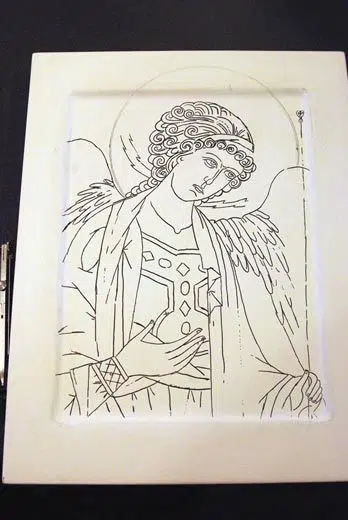

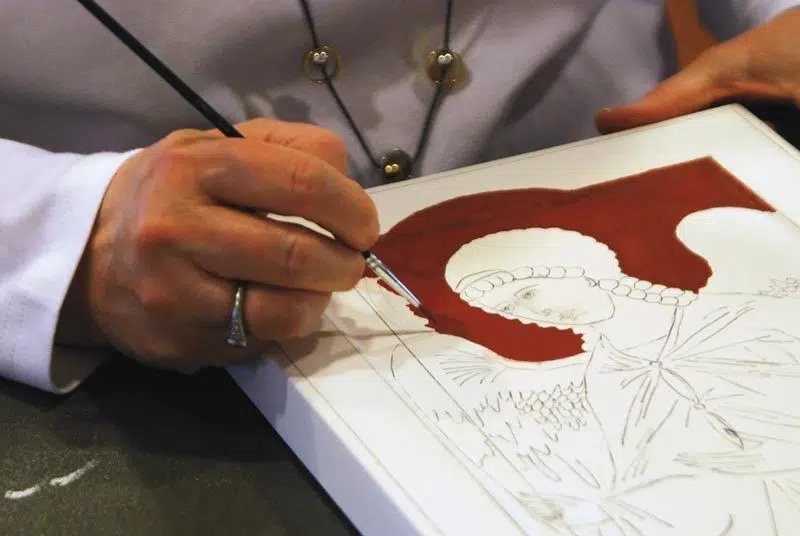

First the icon is drawn onto the surface of a wooden board.

In the workshop, participants used carbon paper to trace the

pattern on the board. Then, the lines were etched into the

surface and areas that were to become gold were painted with

a layer of red bole, a type of clay. After being sanded and

polished, the bole became the foundation for the gold leaf,

which was carefully laid down one small piece at a time.

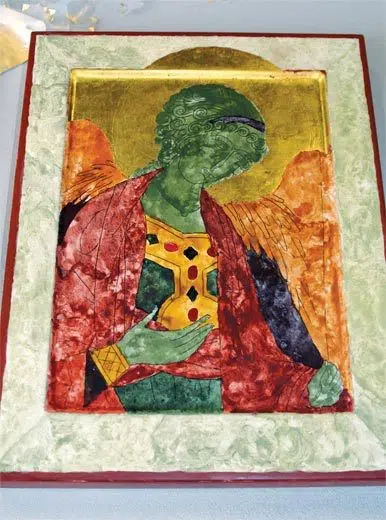

After the gold was in place, the icon was “opened” as the

base colors of egg tempera were painted on the face and

hands, and then everywhere. At this stage, the colors were

dark and one-dimensional. In the next stage, the “lights” –

lighter colors that add shape and volume to the icon – were

painted, with “floats” – transparent layers of color that

even everything out – being applied after each phase. These

lights and floats made it possible to have different hues of

the same color in the icon, giving it a more realistic and

three-dimensional appearance.

The whole process is time-consuming and tedious, and in order

to be effective, it cannot be rushed. The process is also

wrought with deeper meanings. Painting the icon is symbolic

for every individual’s journey toward sanctification. That is

why, for example, the paint is dark at first and gets lighter

at every level, to show a rising from sin.

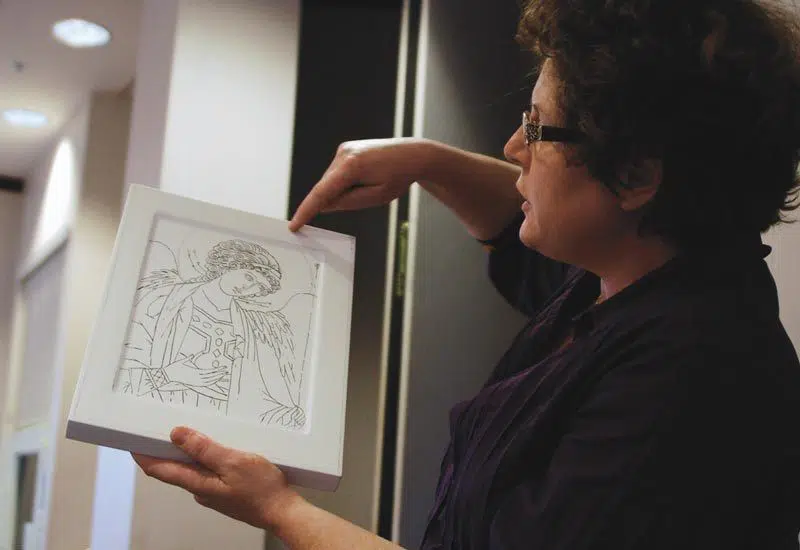

“Each step in making the icon will have a different meaning,”

said iconographer Ioana Belcea, who taught the workshop. “At

each layer, the icon needs to be in harmony. As you move

further in your spiritual life, it is important to be in

harmony. Everything needs to be balanced.”

For Belcea, iconography has been her passion for the past

seven years. Having grown up Catholic in Romania, she had

fallen away from the Church for a while. After coming to the

United States when she was 16, she earned a degree in fine

arts at Rutgers University in New Jersey, but had never

worked as a professional artist.

“I thought there was too much garbage that people put forth

and I didn’t feel like I had anything to say, really,” she

said.

When her son was born, she started to come back to the Faith

and it wasn’t long before she felt the need to create art.

She found a book on iconography and started learning on her

own, but that was just the technical side of icons and she

wasn’t satisfied. Then her mother found an article about an

iconography workshop in Mystic, Conn., at the St. Michael

Institute of Art. Belcea left town for five days to attend.

“It was truly an eye-opener because all of a sudden

everything came together – my artistic background, my return

to the Church, it was intellectually challenging, which I had

found missing in my earlier years, and it was also extremely

rewarding, giving me tremendous insight into a world I didn’t

even know existed,” Belcea said.

After that, Belcea became passionate about learning

iconography and started taking weekend workshops with the

Russian iconographer Vladislav Andreyev at the Prosperon

School of Iconology in New York every few months.

“It was a very slow process,” Belcea said. “It went

hand-in-hand with my spiritual growth and I can really trace

every step of the way, both in the image and in my life.”

Among other things, Belcea said iconography has taught her

patience, discipline and trust in God. Because of her icons,

she has also done a good deal of reading on iconography,

theology, the Scriptures and the writings of the Early

Fathers of the Church.

“I found that as I went deeper into understanding

iconography, not only did I understand Catholicism and how

true it is and how everything in icons and dogma and the

teachings of the Church and so on, how much they are one,”

Belcea said.

Today, Belcea works as a professional iconographer, and has

made three pieces for St. Catherine of Siena Church. She now

hopes to pass on the lessons she learned to her own students

through her workshops. The most recent workshop was the fifth

she has taught in four years.

“I felt like educating people about icons would be a good

stepping stone in preparing them for the same liturgical art

and I also feel like there’s a responsibility where, if

you’re given much, you have to give back to the community,”

Belcea said. “I feel blessed to have been given so much by

the master I have, and this is my own parish, my own

community and I felt I should pass it on.”

During the workshop, Belcea spends a lot of time explaining

the significance of each step. This is one of the reasons why

many workshop participants choose to take part in the

workshop more than once.

“I like the combination of art and spirit,” said Cindy Laird,

who took Belcea’s workshop last year and has been working on

icons ever since, having already completed two.

“There’s something about the process of painting icons that

is very contemplative. It’s very God-centered.”

For Ruth McCully, the workshop this month marked her second

class.

“I really enjoyed it the first time – it allows an

opportunity to step back and step out of the world to another

place to focus on this,” McCully said. “Although we can be

lighthearted in the class, there’s still a lot of meaning as

we’re going through the process, so particularly at Lent, I

think it’s a great practice because it forces you to slow

down.”

Workshop participant Richard Fanelli also enjoyed the

spirituality involved in the icons.

“It helps you to develop inner calmness and it’s a beautiful

piece of artwork that you’re proud to hang on the wall,”

Fanelli said. “I like doing it during Lent because I feel

like it’s a Lenten exercise. It helps you focus on spiritual

things.”

While many people who join the class are not artistically

inclined, even the people who joined to learn about the

artistry found the spiritual aspect of the icons moving.

Mandy Hain said she wanted to learn from Belcea to be exposed

to the ancient techniques of egg tempera, in which egg yolks

are mixed with water and natural pigments to make paint. She

was impressed with the spiritual aspect of the icons.

“It really causes you to meditate on the state of your soul,”

Hain said.

“I think that each person gets something different from it,”

Belcea said. “Sometimes I find that I teach the class and I’m

actually teaching to one person because that one person

needed to hear what I had to say. The others enjoy it, but

that one person is transformed more than the others. That’s

why, when I prepare my classes, I always ask God to help me

put something together that is faithful to that moment.”