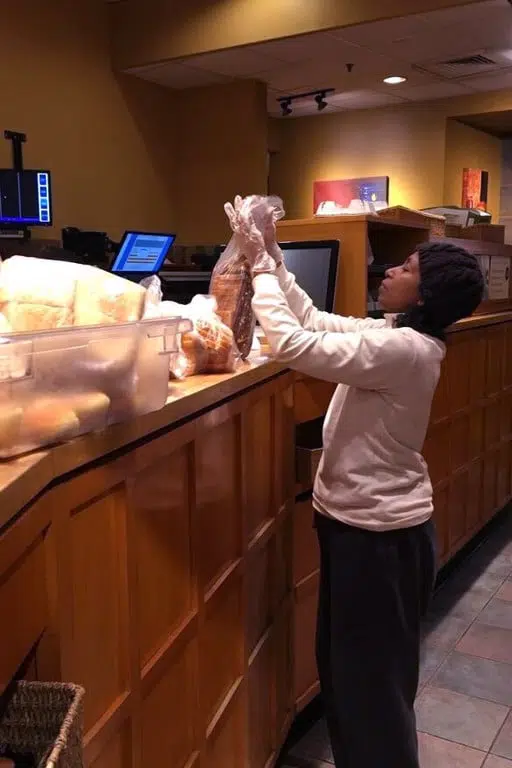

You hungrily scan the rows of plump bagels and

cinnamon-and-sugar covered pastries at your favorite cafe,

carefully selecting the perfect pairing for your midday

coffee or post-Mass outing.

But what happens to the bread-based items at the end of the

day or after they’ve reached their sell-by date?

Much of it likely goes from display case to trash can to

landfill, according to a recent study by the Natural

Resources Defense Council, an environmental action group. The

study found that 40 percent of food in the United States goes

uneaten.

Tossing out edible food does not sit well with Jim McCracken,

a parishioner of St. Louis Church in Alexandria, especially

given that food insecurity across the diocese ranges from 5.2

percent to 17 percent of the population, according to

diocesan Catholic Charites. The U.S. Department of

Agriculture defines food insecurity as a state in which

“consistent access to adequate food is limited by a lack of

money and other resources at times during the year.”

To divert at least some food from landfills into hungry

stomachs, McCracken began what he refers to as a “food

gleaning ministry” 15 years ago. Called “Bread for Our

Brothers,” the ministry is a partnership between the Mount

Vernon Knights of Columbus and St. Louis Parish that brings

unsalable bread products from five food vendors to 20 food

pantries, shelters and churches, including Christ House in

Alexandria, the St. Vincent de Paul food pantry in

Fredericksburg and the Catholic Charities-run St. Lucy

Project distribution center in Manassas, which serves as a

hub for parish food pantry donations. Bread also is brought

to 10 local religious communities, including the Poor Clares

and Poor Sisters of St. Joseph in Alexandria.

Gleaning, referred to multiple times in the Bible, is the

custom of allowing the poor to follow reapers in the field

and gather the fallen but edible food. McCracken says the

term is fitting because his ministry not only collects bread

that would otherwise be wasted but also fulfills the Gospel

call to care for the poor and “live with charity.”

Bread for Our Brothers began while McCracken was attending

Trinity University’s Education for Parish Services program in

D.C. A classmate and Maryland Knight who had been collecting

extra bread from an industrial bakery and bringing it to food

pantries in Maryland and Washington was looking for another

place to distribute the loaves.

McCracken volunteered to help, and he began transporting

bread to the nonprofit United Community Ministries in

Alexandria, where he’d been teaching adults computer skills.

“I’d fill up my van with all this fresh bread, and the

windows would steam up,” recalled McCracken. “It always

smelled like a bakery.”

The ministry has grown over the years, with around 45

volunteers now gathering a mix of pastries, artisan breads,

bagels and rolls from three Safeways and one Panera Bread

store near St. Louis Church. They collect sliced bread from

the Lorton and Alexandria depots of Bimbo Bakeries USA, the

largest bakery company in the United States; Vermont Bread

Co., an organic baked goods supplier; and the Schmidt Baking

Co., which delivers to Giant grocery stores in Lorton and

Springfield.

Some of the bread has been slightly dented or is excess. Much

is collected on or near the sell-by date.

McCracken said the sell-by date is misunderstood. “Many

Americans think of a sell-by date as an expiration date, but

that’s not true,” he said. They are meant to tell grocers how

long to keep items on shelves.

The “rescued” bread is still “fresh and good to eat,” said

McCracken.

Knights and volunteers hailing from St. Louis and other local

Christian churches collect the bread several days a week and

transport it to the various locations using a truck lent by

the St. Lucy Project. Most of the bread comes from the

Vermont Bread Co. and Bimbo, and McCracken estimates a total

of 2,500-3,500 bread-based items are donated each week.

It’s a simple ministry at the service of bigger efforts to

feed the hungry, said McCracken, who retired in 2003 as a

federal employee at the National Institute of Standards and

Technology. But McCracken is grateful to be part of an effort

that saves edible bread from going to the landfill and

nourishes people. “It’s an act of mercy,” he said. “It’s an

extension of what Pope Francis is calling us to do.”