A suicide reverberates with an added layer of loss and

heartbreak when the life ended was a young one. And there

have been many such deaths in the news recently.

On April 13, a College of William and Mary student killed

himself, the fourth to do so this year at the Williamsburg

university. Last year, Fairfax’s W.T. Woodson High School

grappled with its sixth suicide in a three-year span.

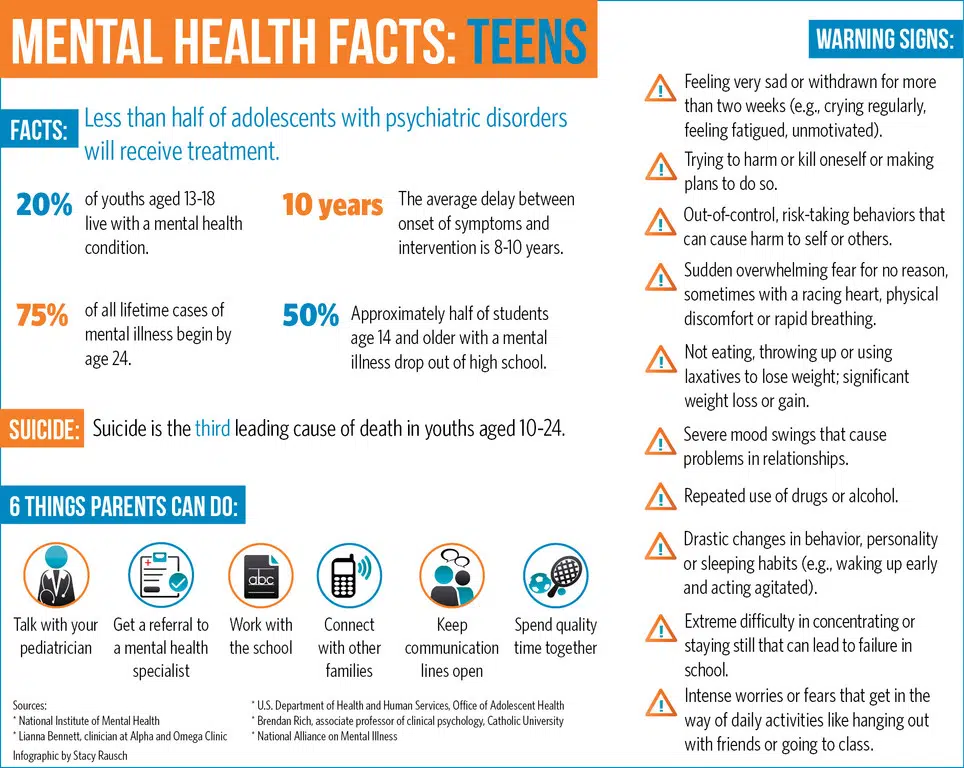

With suicide the third leading cause of death in youths ages

10 to 24, it is startling that less than half of adolescents

with mental health problems receive treatment, according the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of

Adolescent Health. While the majority of mentally ill teens

will not commit suicide, lack of professional help deepens

and prolongs suffering.

So what are the reasons for this lack of treatment, what are

the warning signs, how are diocesan high schools helping, and

what can parents do to offer support?

The silencing power of stigma

Local Catholic Angela Henderson’s daughter, Jane (names have

been changed to protect the daughter’s privacy), was

diagnosed with depression when she was 12. But it took the

family about a year to realize her symptoms were more than

normal teenage angst.

“At first we thought (her yelling and tears) might just be

typical teenage acting-out or hormones,” said Henderson.

The challenge of sorting out mental illness from typical teen

behavior is one reason for delayed treatment, or none at all,

said Alpha and Omega clinician Lianna Bennett. Alpha and

Omega Clinics, based in Maryland and Virginia, integrate

psychology with the Catholic faith.

Additional obstacles to treatment include poor access to

care, especially in rural areas, and the high cost of

psychological services, according to Brendan Rich, associate

professor of clinical psychology at Catholic University in

Washington. “Psychological services are not always seen as a

necessity by insurance companies,” Rich said.

However, mental health experts agree that the No. 1 reason

adolescents do not receive treatment is the stigma that still

surrounds mental illness. Some see psychological problems as

moral weakness or lack of self-control. Teens, naturally

prone to be more concerned about appearances, feel the weight

of such negative perceptions most acutely, Rich said.

Adolescents might even view a therapist’s office as “a place

where crazy people go,” said Bennett.

The stigma is intensified by the way media often link violent

behavior and mental illness.

“People with mental illness have the same level of aggression

and antisocial behavior as the general population, but

unfortunately we talk about mental illness usually only after

an antisocial, aggressive act,” Rich said, citing the recent

tragedy of the Germanwings co-pilot who was treated for

depression and last month crashed a plane killing 150 people.

According to HHS, only 3 to 5 percent of violent acts can be

attributed to mentally ill individuals.

To decrease stigma, Rich and Bennett encourage parents to

realize that mental illness, like physical illness, is not a

choice and to be cognizant of the language they use and

attitudes they convey when discussing it.

“If we view mental illness as a weakness or depression as

something people need to ‘get over,’ our children will be

much less likely to seek us out if they experience

struggles,” said Bennett. “We need to have compassion for

those who are struggling with mental illness; as our

understanding of the brain and neuroscience grows, we realize

that biology has a strong impact on mental health.”

“Once we started to be more open (about Jane’s depression),

we learned others had struggled with similar things, but had

kept it a secret,” Henderson said. “It was a relief to know

that we were not alone.”

Warning signs

It was a Sunday night and Jane decided a homework assignment

needed to be redone. Her distress grew into a tantrum that

continued to escalate.

“I was just holding her, her heart pounding, until her

breathing returned to normal,” Henderson said. “Afterward,

she said, ‘Mom, that was scary.'”

It was frightening for Henderson, too, and the panic attack

served as a catalyst for treatment.

Because adolescents typically don’t seek treatment on their

own, parents play a crucial role in identifying warning signs

and connecting teens with support, said Joel Sherrill,

program chief of the Child and Adolescent Psychosocial

Intervention Program at the National Institute of Mental

Health.

“There are expectations that teenagers assume more

independence and that their dependency on parents goes down,

… but parents are still very important in their

child’s life,” he said.

Warning signs include “a change in how a youth interacts with

peers, if they are becoming more withdrawn or if their class

work is suffering,” said Sherrill.

Additional indicators (see infographic) include a change in

sleep or eating patterns, difficulty concentrating,

tearfulness and not finding pleasure in activities once

enjoyed.

Symptoms vary depending on the nature of the mental illness,

with the most common illnesses being depression and anxiety

disorder. Teenagers also commonly struggle with eating

disorders; Internet addiction, including to pornography and

video games; self-harm, such as cutting; and the effects of

bullying.

For many of her young clients, at the core of their illness

is “a feeling of worthlessness,” said Bennett.

Schools on the frontlines

Along with parents, schools also can help teens emerge from

the darkness of mental illness.

“Schools often have a good sense of a student’s normal

functioning, and many schools … are the first step in

getting in touch with resources,” Sherrill said.

“Our teachers are very much on the frontlines and

encountering early symptoms,” said Dan Kochis, director of

counseling at Paul VI Catholic High School in Fairfax.

Not all youths feel comfortable initiating conversations

about problems with their parents, so teachers, coaches and

school counselors “offer them a chance to speak with other

adults they trust,” said Erin O’Leary, director of counseling

services at Bishop Ireton High School in Alexandria.

The diocesan Catholic Schools Office provides a list of

specialists based on suggestions from teachers and parents,

and several schools supplement it with additional resources.

If a family can’t afford treatment, the high schools often

refer them to Catholic Charities, which offers therapy on a

sliding scale.

Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington hosted a mental

health expert on a professional development day to discuss

warning signs. Monthly coffees for parents often focus on

mental health, and a fall assembly addresses respect and

bullying.

Paul VI has a part-time pastoral counselor as well as a peer

mediation ministry. “If someone is struggling with

depression, we want them to know they are not alone,” said

Kochis.

All four diocesan high schools also offer something

intangible but equally important: a holistic sense of the

human person.

“Our Catholic mission is to form the mind, body and spirit,”

Kochis said. “If the whole person includes the cross of

mental illness, that’s OK. That’s the child of God and that’s

how they’ve been given to us, and we will support and provide

for them.”

“Being part of a community that cares, that responds and

prays makes all the difference,” added Tricia Laguilles,

director of guidance at Saint John Paul the Great Catholic

High School in Dumfries.

Partners in the struggle

Parents frequently blame themselves for their child’s mental

illness. “As a parent you wonder if they’d just had a happier

childhood, different parenting or if you’d prayed harder – if

that would have made a difference,” Henderson said.

Yet Bennett said parents should not blame themselves. A

mental illness “is not a sign that a family is bad or broken

or worse than any other family,” she said.

Of course family dynamics sometimes contribute to a teen’s

mental illness, said Bennett, but parents almost always are

integral to successful healing. The most important thing

parents can do, she said, is to ensure their teen receives

treatment.

Bennett encourages parents to talk with their child if they

believe something might be wrong. “Parents sometimes worry

that if you talk to them about depression or self-harm you’ll

put the idea in their head,” she said. “That’s false; it does

not increase the risk.”

Bennett said it’s important for parents to pay attention to

changes in mood and behavior and to continually work on their

relationship with the child. Take time to have fun with your

son or daughter, she said. “If they feel like you enjoy being

around them, they are more likely to open up.

“Teens can be rough around the edges sometimes. Our job as

adults is to not let them pushing our buttons activate us.

Remember, teens are going to say stupid things; our job is to

be steady for them.”

Faith can also be a powerful source of healing for

individuals with mental illness as well as those who support

them.

“Remembering that we are a child of God is important for all

diseases, but especially when dealing with mental illness,”

Henderson said.

It therefore was painful to realize that depression had taken

a toll on Jane’s faith. “With all the darkness she

experienced, she has a hard time believing in a loving God

…. and rejected anything church-related for a long

time.”

Henderson did not push her daughter to go to church, “but I

kept believing, and friends and family kept praying for her.”

Then about a month ago, Jane – now 15 and “relatively stable”

– said she wanted to try and go back to church. The family

went to Easter Mass together, attending an early service

since Jane struggles with social anxiety.

“Halfway through Mass, she snuggles into me and says, ‘This

is beautiful, Mom,'” said Henderson. “That was my Easter

gift.”

Henderson said she’s thankful for the treatment that’s helped

Jane emerge from the abyss of depression. And she’s also

deeply grateful for the ability to turn to God.

“There is struggle and pain like with any other disease,”

said Henderson. “Faith doesn’t cure the problem, but it is a

supportive companion. And it allows for these moments of

grace that come after the struggle.”

Mental health resources

Suicide hotline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or go here for a

live webchat

Alpha and Omega Clinic: 301/767-1733 or click here

Catholic Charities’ Family Services: 703/224-1630 or go here

National Alliance for the Mentally Ill: nami.org

Boys Town, a Catholic

organization with resources on parenting and child behavior