VATICAN CITY – A little bit of spring cleaning or a much needed renovation can turn up the most unexpected things – especially if you’re sprucing up or digging through the Vatican.

Home of hundreds of thousands of artifacts, archived documents, ornate frescoes, plaster niches and underground tombs, it can be heavenly for a treasure hunt.

The latest precious find came after restorers tackled the Borgia Apartments, which were decorated by the Renaissance master, Bernardino di Betto, better known as Pintoricchio.

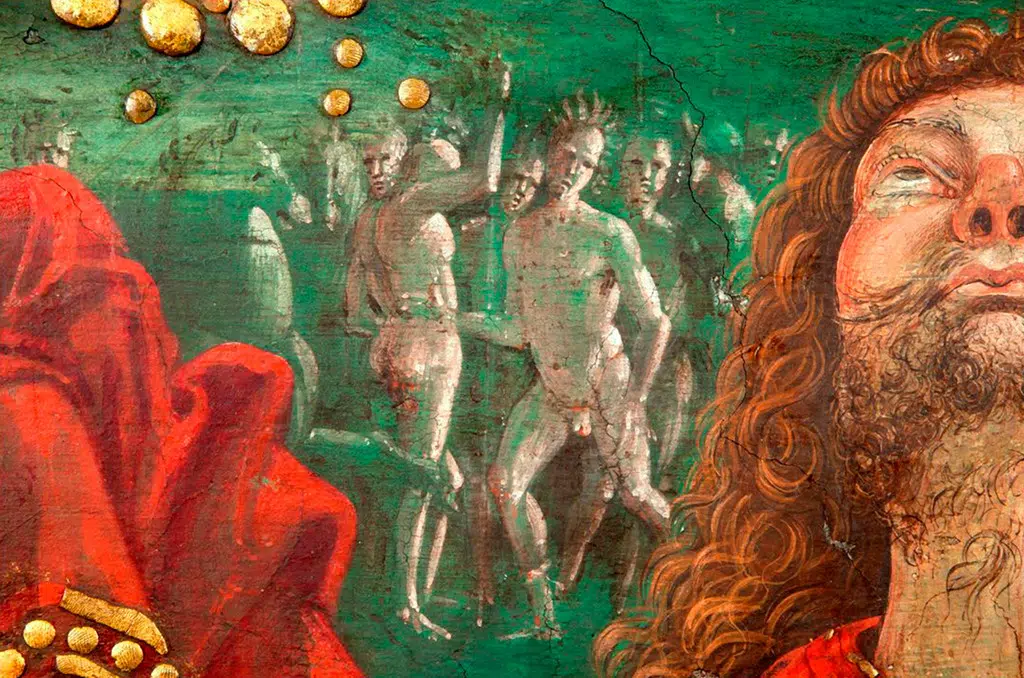

The Vatican Museums’ director thinks what restorers found under soot and successive coats of color are the very first painted depictions of Native Americans.

Antonio Paolucci told the Vatican newspaper the recently unveiled portion of the fresco shows a cluster of “nude men, ornate with feathers, in the act of what seems to be dancing.”

The mysterious men appear in the background under a Risen Christ in Pintoricchio’s fresco of “The Resurrection” in the Room of the Mysteries of Faith in the Borgia Apartments.

Paolucci said it wasn’t inconceivable that the Renaissance painter included the then-recently discovered inhabitants of the New World.

Spanish Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, whose country of origin was funding the voyages, was elected Pope Alexander VI in 1492, just a month before Christopher Columbus sighted land in the Americas.

“The Borgia pope was interested in the New World,” Paolucci said. The process of decorating the apartments finished in 1494 and it is unlikely the pope “was in the dark about what Columbus saw when he arrived to the ends of the earth.”

Fresco restoration seems to be a lot like unwrapping a grab-bag gift: You never know what you’ll find by peeling away layers of centuries-old grime, water damage or botched painting repairs.

Experts working on the Vatican’s catacombs of St. Thecla uncovered what’s believed to be the oldest known depiction of St. Paul and announced the find just a week before the apostle’s feast day on the tail end of the Pauline year in 2009.

Blasting off limestone encrusting the painted ceiling with a laser revealed a fourth-century portrait that was so detailed and stunning “it took the restorers’ breath away,” the Vatican newspaper had reported.

The image of a bald man with a stern expression, a high forehead, large eyes, distinctive nose and a dark tapered beard matched images of St. Paul from later centuries, experts said.

Continued cleanings in the burial chamber in 2010 exposed what experts claimed were the oldest existing paintings of Sts. Peter, Paul, Andrew and John.

If just scrubbing and scraping can lead to surprises, imagine what happens when advanced technology lets you snoop in places that had been inaccessible for centuries.

Archeologists had always been curious to find out what was inside an enormous marble sarcophagus – the presumed tomb of St. Paul, in Rome’s Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls.

Because part of the sarcophagus is wedged beneath building material and opening it would have meant demolishing the papal altar above it, it had never been opened in the 20 or 19 centuries it was there, Cardinal Andrea Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo, the basilica’s former archpriest, said in 2009.

Vatican engineers tried using an X-ray, but the 10-inch-thick marble was impenetrable.

Finally a very small perforation was drilled into the marble to insert a small probe and withdraw fragments of what was inside. Experts said they found traces of purple linen, a blue fabric with linen threads, grains of red incense and bone fragments that date from the time of the apostle’s death.

Pope Benedict XVI announced the historic findings to the world on the eve of the saint’s feast day saying “This seems to confirm the unanimous and uncontested tradition that they are the mortal remains of the Apostle Paul.”

But you don’t have to restore artwork or dig underground to find hidden gems.

Simple Vatican offices and storerooms are a packrat’s paradise with one man’s scrap being another man’s treasure.

Archivists of the Fabbrica di San Pietro, the Vatican office responsible for the basilica’s construction, repairs and maintenance, have mountains of manuscripts, antique receipts and crinkled memos to sort, curate and preserve.

In 2007, they discovered a rare sketch by Michelangelo Buonarroti on the back of a torn piece of paper scribbled with workmen’s notes.

Some believe this 1563 drawing of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica may be the last surviving example of the Renaissance master’s work before his death in 1564.

His working sketches of the basilica are rare because he regularly ordered the drawings to be destroyed or burned them himself to prevent their sale on the market.

Made with dark red chalk lines, the sketch shows a partial plan of the columns of the cupola drum and was probably used to give foremen at the quarries an idea how the stone would be used in the structure.

But, as sometimes happened, the buffalo-pulled wagon carrying the stone was blockaded by angry landowners, who were upset the heavy loads would damage their property. The basilica employee traveling with the consignment tore the design into a smaller sheet and wrote on the back about his predicament to his superiors in Rome.

Someone in the basilica’s business office dealing with paying out damage fees used the same sheet, but scribbled a draft of their official order of payment – on top of the design.

The note-cum-sketch was thus filed away in a sea of documents in the accounts office archive to be discovered more than four centuries later.