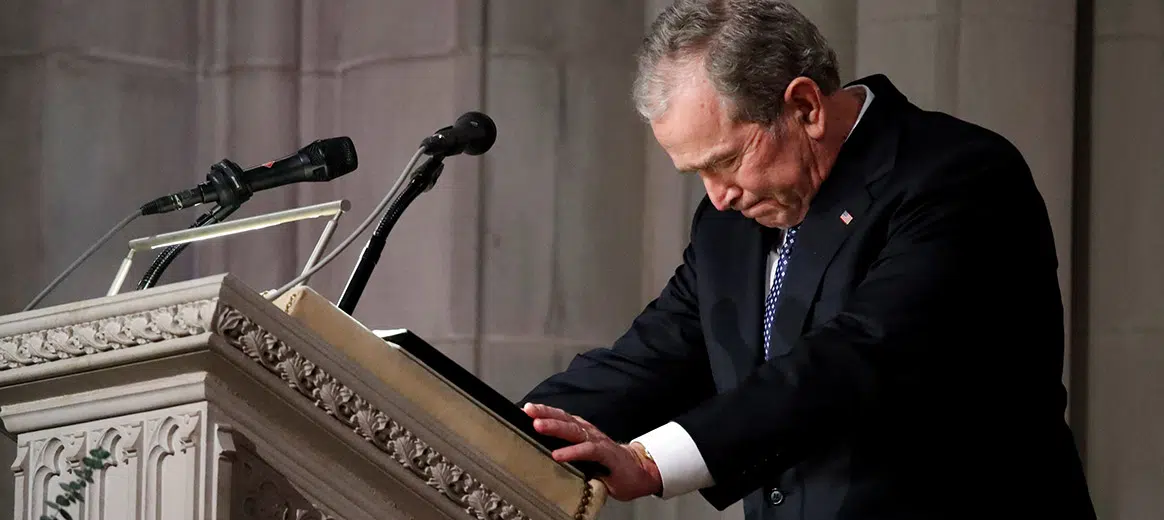

Honestly. What father — having listened to President George W. Bush’s (“W”) majestic 12-minute eulogy for his father and the 41st president, George H.W. Bush — could not permit himself to hope in his heart of hearts that his child might display such respect and affection for him (“the best dad a son or daughter could ask for”) upon his own death?

But that’s not all. No thinking, clear-headed man can walk away from the George H.W. Bush eulogies without undergoing his own full-scale examination of conscience, or review of life. The examination was all the more searing by virtue of its expanse: one was compelled to evaluate one’s own life as a man of faith, a husband, father, friend and citizen. And in each of these departments, George H. W. set the bar high, or to use a naval term he knew well: CAVU (ceiling and visibility unlimited). That’s high.

If you doubt me, simply watch some videos of the funeral coverage. Here are a few of the people I saw overcome by emotion: his sons and their wives, his grandchildren, friends, staff, colleagues and former political adversaries. Members of the media covering the funeral cried. Fathers and mothers and children waving flags in the rain in small Texas towns cried as his flag-draped casket passed by train.

To prepare for confession, I like to use a good examination of conscience. Thinking through simple questions like, “Have I treated people, events, or things as more important than God?” help to identify what impediments I need to confess in my encounter with Jesus Christ in the sacrament.

And yet, watching eulogist after eulogist overcome with emotion, I sensed that I was being invited to conduct a high octane, turbo-charged examination of conscience. Each eulogy implicitly offered its own penetrating questions: about the depth of one’s marriage, the caliber of one’s fatherhood, the loyalty of one’s friendships, the vigor of one’s citizenship, or the vitality of one’s own prudence, temperance, justice and courage.

H.W., I’m sure like all of us, had his flaws. Yet judging from the funeral, he applied the truth of I Peter 4:8 in his own life: “Above all, let your love for one another be intense, because love covers a multitude of sins.” Consider, as an example, the bedrock of his marriage: “[E]very day of his 73 years of marriage,” W. shared, “Dad taught us all what it means to be a great husband. He married his sweetheart. He adored her. He laughed and cried with her. He was dedicated to her totally.” His gravestone reads simply, “He loved Barbara very much.”

At the Bush funeral, America did not don black clothes, walk into a church, mouth the words to a few old hymns, smirk at some politicized eulogies, and get back into the car, dry-eyed. At the Bush funeral, America instead sat in awed silence as it beheld the sweeping consequences of one man’s quiet faith, his 73-year marriage, his humility, discipline, love, humanity, decency and courage. America was anything but dry-eyed.

The examination of conscience reached a crescendo when three simple questions of President George H. W. Bush, cited from his 1989 inaugural address, rang forth during one eulogy: “We cannot hope only to leave our children a bigger car, a bigger bank account. We must hope to give them a sense of what it means to be a loyal friend, a loving parent, a citizen who leaves his home, his neighborhood and town better than he found it. What do we want the men and women who work with us to say when we are no longer there? That we were more driven to succeed than anyone around us? Or that we stopped to ask if a sick child had gotten better, and stayed a moment there to trade a word of friendship?”

To paraphrase one decent man of blessed memory, let future generations say that we stopped and stood where love and duty required us to stand.

Johnson is director of evangelization for the Diocese of Arlington.